Your cart is currently empty!

Building a Dutch-Korean precision bridge

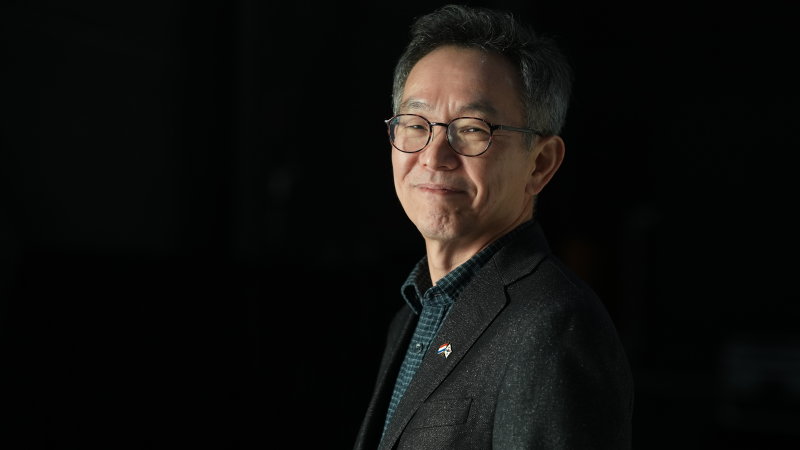

Hak Kyung Sung and his Sobujang Forum, a group of several hundred Korean tech companies, is seeking close collaboration with Dutch partners. Bits&Chips sat down with “Dr. Sung” at last week’s Precision Fair to talk about the opportunities that are on the horizon when Dutch and Korean companies work together.

Hak Kyung Sung knows what he’s talking about when he speaks about mechatronics. He spent almost thirty years at Samsung Electronics, rising through production engineering, product development and manufacturing roles to a position of vice president. In his final years at the Korean behemoth, he and his team of 150 engineers were responsible for the production of The Wall, a luxury television product line with unmatched brightness and contrast. The TVs consist of tiles, each carrying two million micro-LEDs measuring 50 by 50 micrometers. In every tile, all two million LEDs must be placed one by one. Sung’s team delivered the very first version of The Wall, a 91-inch 4K television with 49 tiles.

Sung studied mechanical engineering in Korea and did a PhD at the Tokyo Institute of Technology. “When I was an undergraduate, my father and mother were in Japan and I visited them several times. That’s one of the reasons why I went to Tokyo for my PhD.” In those days, most of his Korean peers chose the United States for doctoral studies. That divergence later gave him a distinct advantage in working together with Japanese tech companies.

From the moment he entered Samsung, Dr. Sung gravitated toward equipment-intensive, high-precision domains. Over the decades, he worked in several business units – semiconductors, displays, electronics and battery manufacturing – always on the engineering side. “At Samsung, I mainly did problem solving, and manufacturing equipment and production line design in the manufacturing R&D center and business units.” He got to lead engineering teams of up to 400 people.

Sung’s career reflects the manufacturing philosophy that still underpins Korea’s semiconductor and display industry today: high precision, high throughput and aggressive ramps of new process technology. At Samsung, he and his multidisciplinary team worked on a wafer transport robot, mold and surface mount systems and a curved mobile phone production line, among other things. His last projects included developing the manufacturing process for The Wall in Korea and setting up mass production lines in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam.

Japanese connection

Dr. Sung’s close relationship with the Land of the Rising Sun spans more than three decades, beginning with his PhD years in Tokyo. He explains that although Japan and Korea have a complicated history together, industry ties between the two nations have always been strong. “They have a history comparable to that of the Netherlands and Germany. Similarly, the industry in both countries is very well connected. Korea basically learned a lot from Japan,” he notes.

His Japanese connection made Dr. Sung Samsung’s natural liaison to suppliers in that country. Over the years, he built a wide network in Japan’s manufacturing ecosystem, encompassing SMEs, component specialists, universities and venture capital firms. That network proved crucial when he started coordinating open-innovation activities within Samsung.

Through the investment in a Japanese VC, Sung was introduced to a thousand Japanese startups and SMEs looking for business opportunities with Samsung. “I was the central point of contact for all these companies,” he says, describing what he recognizes as an early form of open innovation. This cross-national industrial experience became foundational for the organization he would set up after his retirement: the Sobujang Forum.

Throughput

To be able to manufacture the micro-LED televisions, Dr. Sung’s team worked together with hundreds of small and medium-sized companies in Korea and Japan. The Wall replaces conventional LCD or OLED pixels with matrices of millions of individual LED chips. “In micro-LED TVs, each pixel is a single LED. It has very high quality. It’s difficult to produce. It has to be very uniform without defect,” he explains.

For an 8K Wall display, you need 24 million chips on 81 tiles. Every one of these LEDs must be transferred from a donor substrate to the final display panel. The manufacturing process tolerates neither defects nor misalignment. The level of precision, throughput and process stability required is extreme. When asked whether the chips were internally sourced, Sung’s answer is disarmingly practical: “We use Taiwan’s LED chips. Samsung also has its own LEDs, but the ones from Taiwan are cheaper.”

The transfer technology is where his team excelled. “The LEDs were on glass substrates and were then transferred directly to the display panel,” Sung points out. This required entirely new pick-and-place equipment designed specifically for micro-LED mass transfer. “Making this manufacturing process was my team’s specialty,” he notes. “My team was responsible for developing the micro-placement machines, including the setup of the manufacturing line.”

Throughput was the central challenge. “With only one transfer machine, it would take one month to assemble a TV,” Sung explains. At Samsung, they parallelized the process, resulting in modules that produce one tile in twenty minutes.

The manufacturing line is now operational in Samsung’s Ho Chi Minh City factory, supported by development lines at Samsung Digital City in Suwon. Creating this full ecosystem required close collaboration with more than a hundred SME suppliers. As Sung puts it, “When Samsung wanted to develop micro-LED TV, the bottleneck was the manufacturing.”

Helping SMEs

Dr. Sung is now leveraging his engineering leadership in ultra-high-precision equipment, throughput-driven process design and working together with dozens of SME suppliers in his work with the Sobujang Forum, which he founded after retiring from Samsung. This non-profit organization consists of 370 members, including 250 SMEs, investors and academic groups. The name is derived from three Korean words: “so” (material), “bu” (component) and “jang” (equipment). Together, they reflect the full supply chain of Korea’s manufacturing ecosystem.

Sung repeatedly emphasizes how dependent large Korean tech firms are on small, specialized suppliers. “When I developed micro-LED televisions, I needed the help of many small companies. I actually had 10,000 business cards,” he says. “After Samsung, I decided I wanted to spend my time helping SMEs. All my work is about helping them.”

He describes two motivations for founding the forum. The first is industrial: he saw that SMEs often lacked the competencies and access required for scaling. “It’s filling a competence gap of the SMEs. That’s the first goal. Big companies have resources, but small companies don’t,” he explains.

The second motivation is personal – Sung is unusually candid for a Korean industry leader. “When I was working at Samsung, every project was basically supported by SMEs. Because of these SMEs, I could be successful. So after I retired, I thought this would be a good moment to pay back. I’m Christian. I think this is my vocation, helping others who need help.”

Urgency to diversify

The Korean economy is facing headwinds. Competition with China is intensifying, and several Korean tech sectors – including displays, batteries and even semiconductors – have recently endured downturns. Due to new American policy, exporting equipment and material to China has become more difficult and large Korean conglomerates are investing more heavily in building production lines in the US instead of Korea. “Many Korean companies are in trouble,” Dr. Sung noted in his talk at the Precision Conference in Veldhoven.

Yet, Sung remains optimistic. He points to the rebound in AI-related semiconductor demand, including Samsung’s decision to restart major fab expansions. “Samsung is restarting its fab and plans to build more fabs in Pyeongtaek. For me, that’s a sign the market is picking up,” he says. The AI semiconductor sector will also provide new market opportunities for SMEs as new packaging materials and processes will be required, such as glass core substrate and die bonding technologies.

For Sobujang, this environment reinforces the urgency to diversify. “Small Korean companies have to find new customers and seize the new business to remain in the high-tech manufacturing business,” Sung explains. That’s why 2025 is a pivotal year. “In the Sobujang Forum, I declared that this year we have to find new customers, new business in Korea or abroad.”

Complementary strengths

This is where the Netherlands comes in. Last February, during a matchmaking event at Semicon Korea supported by the Dutch embassy, Dr. Sung encountered Dutch high-tech companies at scale for the first time. He was surprised by their mechatronics excellence. With his background in control engineering and industry experience, he was impressed by what they demonstrated.

His findings resulted in a shift in Sobujang’s international focus. For 2025, Sung identifies three priority countries for Korean SME collaboration: the Netherlands, Japan and Vietnam. The Netherlands comes first. The reason is clear: “The Netherlands has advanced technology that Korea needs, especially in precision and throughput. Korean companies can improve their equipment by working together with Dutch companies.”

Sung also sees alignment in market goals. Dutch suppliers want a stronger presence in Korea’s semiconductor ecosystem, to diversify their market from incumbent clients in the Netherlands, the US and Japan; Korean SMEs want access to the advanced mechatronics and motion control expertise that Dutch companies have accumulated around ASML and other high-tech clusters. The Korean companies have mass-production expertise and a strong network with Korean chipmakers. These complementary strengths can form the basis for concrete collaboration models.

Success stories

According to Dr. Sung, collaboration can take several shapes. The first model is joint system development, combining Dutch motion control or mechatronics components with Korean system-level equipment. “Dutch technology providers and Korean equipment makers can work together to find new markets. For instance, we can target semiconductor production lines in Japan, using Dutch motion control with Korean equipment.”

A second model is contract engineering. Dutch firms with strong engineering – he mentions companies like Demcon and Prodrive – can support Korean equipment builders. “These models are quite new for Korean equipment makers. But we, together with Dutch companies and the Dutch embassy in Seoul, are trying to convince them,” Sung says.

A third, longer-term model involves joint ventures and shared revenue. “If these steps in contract research are successful, the next stage I can imagine is developing joint ventures and sharing the profit,” Sung notes.

Delivering successful collaboration cases is crucial. Korean industry culture is strongly shaped by so-called “fast follower” dynamics. “If I can show two success stories to Korean companies, it’s easier to persuade others. Once they see the chance, almost everyone jumps on it,” Sung says. The success stories don’t need to reach commercialization. “If they meet an interim target, that’s already a success story I can tell others.”

Sobujang is currently tracking four Dutch companies with ten active or developing projects with Korean counterparts. “If two of these cases are successful enough to present as a success story, then the Korean industry will follow.”

Unique role

In both this interview and his conference talk, Dr. Sung repeatedly describes Dutch mechatronics as being at a level he didn’t fully appreciate until recently. He cites control engineering, motion systems, high-precision stages, sensing and the systems engineering capabilities developed around the semiconductor equipment sector as differentiators. “You have very, very good high-end fundamental technologies based on science. I was really surprised when I saw that.”

These capabilities directly match the needs of Korea’s equipment-building ecosystem. Korean companies often excel in cost performance, production speed, rapid scaling and reliable equipment manufacturing. However, they increasingly face global markets where nanometer precision, advanced motion control and high-end metrology are required – domains where Dutch firms have decades of embedded expertise. “We’re complementary.”

Sung’s ambition is explicit: to build a strong, stable, mutually beneficial bridge between the Korean and Dutch high-tech ecosystems. He sees precision mechatronics as the ideal foundation for this collaboration. At this year’s Precision Fair, he brought a delegation of 24 people from 15 Korean companies. “They’re looking for new customers, new technology and new collaboration partners,” he notes. By next year, he expects many more – if the first success stories materialize.

The Netherlands, in Sung’s view, can play a unique role in the next chapter of Korea’s SME-driven equipment industry. And Korea, with its immense manufacturing capacity and deep integration with global semiconductor supply chains, offers Dutch SMEs and engineering firms a route into major Asian markets. Even after only his first visit to the Netherlands, his conclusion is clear: “There are very good opportunities for collaboration.”