EU’s scaling of battery manufacturing capacity in trouble, says auditor

The EU risks falling behind in its bid to become a global battery powerhouse, according to a report by the European Court of Auditors (ECA). As a result, Europe risks having to push out the switch to electric vehicles by 2035, not being able to meet long-term sustainability targets and/or falling behind China and the US.

Europe isn’t the only industrialized region facing this threat. In 2021, China accounted for 76 percent of global battery manufacturing capacity globally, well ahead of the EU (7 percent), the US (7 percent) and South Korea (5 percent). Moreover, China dominates the upstream battery value chain, including the supply of raw and refined battery materials such as cobalt, lithium, nickel and natural graphite.

Realizing the critical importance of the technology for its automotive and other industries, the European Commission rolled out a battery strategy in 2018, with the overall aim of making “Europe a global leader in sustainable battery production and use.” Backed with billions of euros in incentives, mostly from member states, the Action Plan for Batteries targets expanding annual manufacturing capacity to 1,200 GWh in 2030, up from 44 GWh in 2020.

That would be enough to manufacture 16 million EVs equipped with a 75 kWh battery – sufficient to power an average saloon car. In turn, this should cover future demand in the combined EU, UK and European Free Trade Association territories. New passenger vehicle registrations in this bloc ranged from 11-16 million units over the past decade.

Reaching the 1,200 GWh target faces major hurdles, though, the ECA report says. Lack of access to required raw materials and global competition threaten to throw a wrench into the works. “The EU aspires to become a global battery powerhouse to ensure its economic sovereignty but will it succeed? The odds are not looking good,” ECA audit leader Annemie Turtelboom told Reuters.

Trans-Atlantic

In terms of battery materials, the EU heavily relies on foreign sources. Roughly 80 percent of primary raw materials and 60 percent of refined materials are imported, according to a 2023 study published by the European Commission. Moreover, most imports stem from only a few countries. For example, 68 percent of raw cobalt is sourced from the Democratic Republic of the Congo and 79 percent of the EU’s supply of refined lithium originates in Chile.

Although the EU does have its own mineral resources, member states and the general public are typically not keen on starting mining operations. Even if they are, lead times from discovery to production commencement average between 12-16 years – too long to support the EU’s 2030 target.

Competitiveness is an issue as well. Battery manufacturers will move production to regions that offer more attractive financial incentives. The US, for example, has recently adopted the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which offers support for domestic production of batteries and related materials and components as well as a 7500-dollar tax credit for buyers of US-made electric vehicles. These and other IRA policies sparked a trans-Atlantic dispute and call for a European response.

Overall, the EU’s independent external auditor warns of two potential worst-case scenarios should the EU battery production capacity fail to grow as projected. The first is that the EU could be forced to delay its ban on vehicles with combustion engines beyond 2035, thus failing to meet its carbon neutrality objectives. The second is that it could be forced to rely heavily on non-EU batteries and EVs, to the detriment of the European automotive industry and workforce, to achieve a zero-emission fleet by 2035.

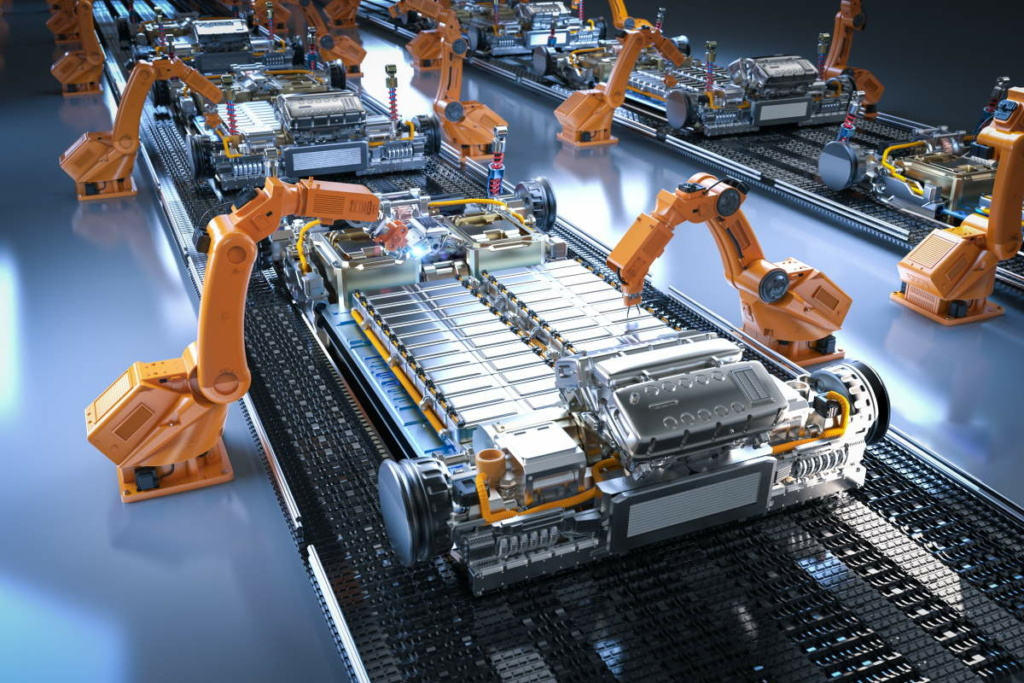

Main picture credit: Phonlamai Photo/Shutterstock