Your cart is currently empty!

GEA tackles cybersecurity energetically

On 20 January 2027, the EU Machinery Regulation will come into force. This successor to the well-known Machinery Directive is designed to improve machine safety further, especially in view of the cyber risks associated with new technologies such as AI, but also digitalization and networking. To be fully prepared for 2027, machine builder GEA, based in Bakel, carried out a Security Risk Assessment with Pilz on a chicken processing production line in 2024. This involved checking the OT network for risks and GEA creating its own guidelines for all future machines.

Anyone who reads the technical requirements related to automation of machine building in the Machinery Directive instantly knows that they were written at a time when cyber-attacks, artificial intelligence (AI) and wireless and remote control hardly existed. Office automation (IT) was secured against hackers and attackers, but the OT networks of the machines themselves weren’t.

When a system operates offline, there’s little to fear from outside cyber-attacks. However, in this day and age, almost every machine is connected to an umbrella network that, in turn, connects to the outside world. In this way, potential entry points have been created for hacking or sabotaging a machine. It might seem reasonable to ask yourself who would want to break into your system, but practice shows that there are indeed reasons for doing so. Criminals who are able to shut down critical machines or cripple entire networks can demand huge ransoms.

In short, developments in recent years have forced a further elaboration of the Machinery Directive into what’s now called the EU Machinery Regulation, or to use its official name: Regulation (EU) 2023/1230. The first final version was published in the EU Official Journal on 29 June 2023, providing a transitional period until 20 January 2027. Until then, all EU member states have the time to make their machines compliant with the new regulation. If they don’t, the machine may no longer be CE marked.

As a feature of the new Machinery Regulation, the definition of safety components now includes software, alongside the familiar components of physical, digital or mixed nature. This means that the term “safety components” now covers not only relays, door switches, safety scanners, light curtains and so on, but also ‘invisible’ software. In addition, a “Protection against corruption” paragraph has been added, so that the regulation now also provides requirements for machine cybersecurity. The main requirement – in terms of security – is that external attacks shouldn’t lead to the failure of safety functions. In practice, this means that manufacturers such as machine builders have to revise their safety concepts in almost all cases.

Security Risk Assessment

Since the publication of the EU Machinery Regulation, both GEA and Pilz have been actively integrating industrial security into machine building. Together, they’ve conducted a Security Risk Assessment as part of GEA’s broader cybersecurity strategy. This assessment is a relatively simple tool to get companies on the road to complying with the new regulation.

“As always, the legal and normative requirements are quite complex, deep and intertwined,” says Thomas Ploeg, sales manager at Pilz. “This requires a shift in thinking: if you look at office automation, IT, there has long been a focus on cybersecurity. Looking at machine automation, OT, there’s significantly more interest in maximum machine availability. These two approaches can get in each other’s way.”

There are other challenges as well. For example, companies have different levels of knowledge and maturity regarding industrial security. Moreover, security items – and especially their consequences – aren’t immediately visible and thus difficult to detect and test, unlike safety issues.

The Security Risk Assessment that Pilz conducted enabled GEA to test and strengthen its own approach to cybersecurity on a structural basis. The findings provided an important basis for the further development of internal guidelines and design processes.

Plan B

Bakel-based GEA (headquartered in Düsseldorf) is a leading supplier to the food, beverage and pharmaceutical industries. Its portfolio includes machinery and installations, as well as advanced process technology, components and services. The company is among the vanguard of machine builders that proactively invest in implementing the EU Machinery Regulation. It views cybersecurity not as a standalone requirement, but as an integral part of design, operations and customer responsibility.

Joost Schepers, senior director Automation & Controls at GEA: “As an established name, we obviously want to be completely ready with everything needed to comply with the Machinery Regulation by 2027. That requires a different way of thinking. Safety is incorporated directly into your design, so you only need to deal with it once. Security, on the other hand, needs annual updating. After all, hackers’ tools and technologies change every day.”

“As a manufacturer, you also need to have a plan B if something goes wrong with your customer’s business in terms of security,” Schepers adds. “Customers require more attention anyway, because maximum safety can only be achieved if they meticulously implement all the measures in the manual. This covers such issues as proper installation of hardware and software, proper use, accessibility for updates, implementation of the company’s own security measures, including a firewall, and so on. If this isn’t in order, you can send updates all you want, but they won’t have any effect.”

Greater understanding

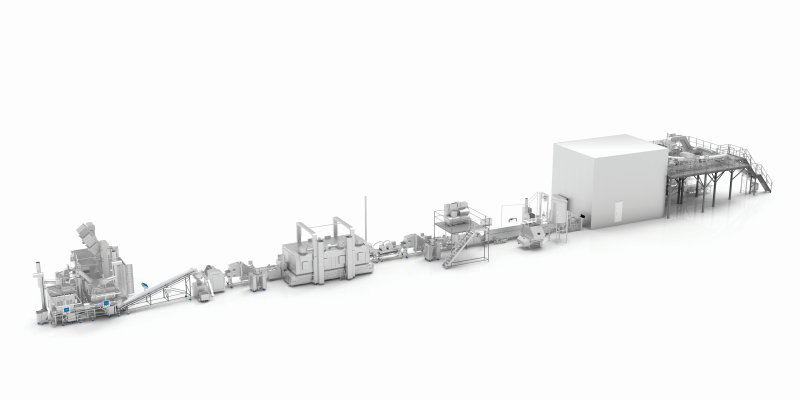

Taking a pragmatic approach, GEA worked with Pilz to conduct a Security Risk Assessment for one complete machine line, which processes chicken parts. These are first marinated in a drum, then coated in breadcrumbs and subsequently pre-cooked in an extended oven until suitable for frying. The line is fully modular, with all modules equipped with their own PLC and communication between them being wireless. “The assessment on this line has further improved our internal knowledge and awareness,” explains Dennis Theelen, software engineer at GEA. “The insights gained have now been translated into concrete internal guidelines, so that future designs take cybersecurity risks into account by default.”

Theelen continues: “It’s equally important to read and interpret the legislation with the help of a specialist like Pilz. This process wasn’t easy, but it has contributed to higher awareness, more knowledge and greater understanding. In this respect, it has provided us with valuable tools to create an inventory of and assess all future machines, lines and modules, in line with our parent company’s cybersecurity roadmap. This should eventually lead to both our processes and the final machines being fully certified in accordance with modern legislation and regulations. To this end, several people are attending various training courses to gain knowledge that they can then apply correctly to their own machines.”

“I’m glad we started on time,” Theelen concludes. “It’s now obvious to us that this is necessary, but we can also see that – for us at least – it’s achievable.”

Top image credit: GEA