Although they work side by side in service of the same business goals, development and operations often experience tension or misunderstanding. This usually isn’t due to poor intent or communication, but rather because of fundamentally different responsibilities, incentives and ways of defining value. Understanding these differences is essential for leaders and practitioners who want to improve collaboration, delivery speed and system reliability.

At a high level, the distinction between development and operations can be understood as a contrast between change and stability. Development teams are primarily concerned with creating new capabilities. They build new software, extend existing systems and translate business ideas into working solutions. Operations teams, by contrast, focus on maintaining and protecting what already exists. Their responsibility is to ensure that systems remain reliable, secure and available to users, often under strict regulatory and contractual constraints.

These differing missions shape the everyday work of each team. Development work is typically forward-looking and organized around planned initiatives. Developers spend much of their time designing features, writing and reviewing code, fixing functional defects and collaborating with product and business stakeholders. The central question for them is what the system should be capable of next. Agile methods like Scrum can effectively be used here as the planning and scheduling of new items match the way of working. Since items are plannable, refinement can be done in advance, supported by priorities set during portfolio management and sprint planning. But this doesn’t work as well for operations teams.

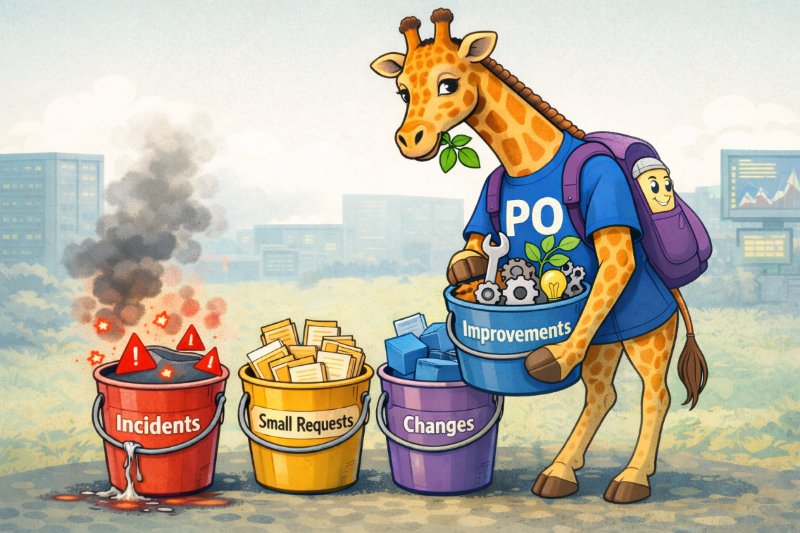

Four workstreams

Last year, I was asked to coach a few teams in a maintenance environment. Once again, I was surprised by the focus on project or development teams. Even in devops environments, a lot of attention goes to the development side of things, while, and I’m not kidding, some teams are known to spend 80-90 percent of their time on operations.

Operations teams are responsible for systems that are already in production and actively used. Much of their time is spent monitoring services, responding to alerts, investigating incidents, managing deployments and ensuring that performance, security and compliance requirements are met. Unlike development work, which can often be planned weeks in advance, operations work is frequently interrupt-driven. Priorities can change instantly when an incident occurs and the consequences of delay are often immediate and visible to the business. Instead of batch-like Scrum steering, Kanban is often used. This resonates better with the ad-hoc nature of incidents.

Although operations teams may occasionally contribute to new solutions, major system changes are often handled by projects or external suppliers. In practice, operations work can be grouped into four main workstreams. The first is incident handling. Incidents don’t create business value; in fact, they can be seen as negative value resulting from errors, insufficient testing or system weaknesses. For users, the real value lies in the absence of incidents. Incident work is highly unpredictable and often urgent, demanding immediate attention.

The second workstream consists of small requests. These include activities such as configuring systems, adding users, managing access rights and performing security or system updates. Because these tasks are explicitly requested, they do carry business value. While they may arrive at any time, they’re usually less urgent than incidents and can often be scheduled. As this work is frequently repetitive, it tends to be relatively predictable.

The third workstream is changes, including collaboration with projects and suppliers. These are improvements to systems that deliver clear organizational benefits and are typically backed by a business case. Changes are generally plannable, with agreed delivery timelines and clear entry criteria before they’re taken into execution.

Finally, there’s team improvement work. This includes efforts to boost collaboration, team culture, automation, tooling and quality practices. While such improvements don’t deliver immediate business value, they make the team more effective over time and help reduce errors and incidents. Improvement work can be planned, but because it often involves new ways of working, outcomes can be less predictable.

Four buckets

When planning operations work, it’s essential to consciously account for these different workstreams. Many teams fall into the trap of constant firefighting. Saving the day by resolving urgent incidents can feel rewarding, and users are grateful in the moment. However, focusing primarily on work that doesn’t create value won’t give sustainable results.

Long-term success comes from improving quality and ways of working so that fewer incidents occur in the first place. As incident volume decreases, cognitive space and time are freed up to deliver real value and invest further in improvements. This creates a positive feedback loop, much like a snowball effect. But it only works if the team deliberately decides to stop running at full speed and make room for improvement.

At my client, we introduced a simple bucket system to make this balance explicit. Each workstream – incidents, small requests, changes and improvements – was given its own ‘bucket.’ Teams and product owners worked together to decide how much capacity they realistically needed for incidents and how much they wanted to reserve for improvement work. These decisions defined the size of each bucket and were aligned with management expectations.

My role as a team coach was to help teams set and adjust these buckets, integrate bucket thinking into planning and support decision-making when buckets overflowed. Equally important was helping teams communicate their way of working to users and project stakeholders. All work needed to keep the system secure, performing and running might not always be easy to explain, but it takes significant effort and must be made visible to account for why the team can’t always directly respond to other requests and has to say no sometimes. Regular evaluation ensured the approach remained effective.

Metrics reinforce the differences between development and operations. Development teams are often measured by delivery velocity, lead time for changes, deployment frequency and feature adoption. Operations teams, by contrast, are evaluated using indicators such as availability, mean time to recover, incident frequency, change failure rates and adherence to service-level objectives.

Understanding these metrics is key to understanding how operations teams work. They should also guide capacity allocation in systems like the bucket approach. Simply fixing incidents over and over again is unlikely to improve either the team or its performance in the long run. True improvement requires intentional investment in stability, quality and learning. Only then can operations teams move from constant reaction to sustainable, high-value contribution.

The operations PO

A product owner in an operations context operates in a world of uncertainty, interruption and risk. Unlike a development-focused PO, who mainly maximizes feature value, the operations PO must continuously balance business impact, technical risk and team sustainability. This requires a mindset that goes beyond backlog ordering and embraces decision-making under pressure.

One of the most critical skills for an operations PO is the ability to assess incident urgency quickly and calmly. This isn’t about reacting to the loudest voice or the most anxious stakeholder, but about understanding real business impact. To do this, the PO needs strong system knowledge and enough technical literacy to grasp what’s failing, what’s at risk and what the likely blast radius is.

Equally important is the ability to separate urgency from emotion. Incidents often come with stress, escalation and incomplete information. A good operations PO asks the right clarifying questions and makes decisions that protect both the users and the team.

Determining the size of the different work buckets – incidents, small requests, changes and improvements – is a strategic responsibility. It requires the product owner to think in terms of flow, capacity and long-term outcomes, not just short-term delivery. Strong operations POs understand the cost of neglecting improvement work. They can articulate why reserving capacity for automation, quality improvements or technical debt reduction isn’t optional but essential for reducing future incidents.

Stakeholders often care deeply about visible outcomes, features, deadlines and immediate fixes, while operations value is largely invisible when things work well. The operations PO finds the courage to defend agreed ways of working and does so without damaging relationships. This also includes saying “no” or “not now” when buckets are depleted and entry criteria aren’t met. When stakeholders understand the consequences of ignoring these, they’re more likely to accept those decisions.

Finally, strong communication includes transparency during incidents. Stakeholders don’t need technical detail, but they do need timely, honest updates. A PO who communicates clearly during crises and follows up with learning and improvement actions afterward builds long-term confidence in the team.